What is autism - substance and risk factors

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or only "autism" is a complex developmental condition that involves constant difficulties in social communication, limited interests and repetitive behavior. While autism is considered a lifelong disorder, the degree of damage to functioning due to these difficulties varies between people with autism.

Currently, the scientific community suggests that several genetic factors may increase the risk of autism in a complex way. The presence of certain specific genetic conditions, such as brittle X chromosome syndrome and tuberous sclerosis, have been identified as particularly increasing the risk of diagnosing autism. Some drugs, such as valproic acid and thalidomide when taken during pregnancy, are also associated with a higher risk of autism. Having close relatives, such as a brother or sister with autism, also increases the likelihood that the child will be diagnosed with autism. The higher age of parents during pregnancy is further associated with a greater risk of autism. [ref. 1]

"Autism disorder" is what most people have heard as a term and perceived as autism. The spectrum of autistic disorders also includes Asperger's syndrome, child disintegrative disorder and an unspecified form of pervasive developmental disorder. All these conditions are now called autism spectrum disorder .

What published scientific data reveals

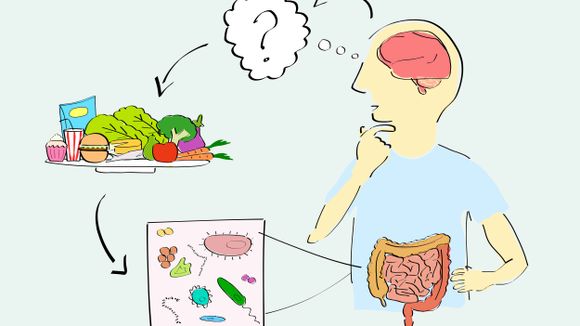

It is assumed that the intestinal microbiome affects various conditions of human health, such as Crohn's disease, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and others with inflammatory component, as well as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This leads to suggestions that changing the microbiome - whether through diet, probiotics or otherwise - can alleviate symptoms. However, a study published in Cell on 11 November 2021 reversed this hypothesis. According to the data in the document, the eating behavior of people with autism spectrum disorder is what determines the composition of their intestinal microbiome. While the findings throw doubt on the potential of ASD treatments aimed at manipulating the microbiome, it is still too early to totally reject them.

Although some individuals with autism disorder have gastrointestinal problems and unbalanced gut microbe or dysbiosis, the evidence that this contributes to ASD symptoms is inconclusive. This is the position of co-author of the study Chloe Yap, a research clinician in the Neurogenetics Laboratory Jake Gratton of the Mater Research Institute, University of Queensland. For example, animal studies showing that carrying certain microbes into mice can alleviate behaviors similar to ASD are difficult to interpret, Yap says, because "rodents don't get autism."

According to Kevin Mitchell, a neurobiologist and developmental geneticist at Trinity College Dublin, there are things we can measure in animals that humans claim to be associated with autism in some way, but the evidence base for this is very weak. As for research and experiments in humans, according to Yap, they were generally "small and not large enough to extract definite conclusions, and the results are actually quite variable."

To clarify the issue, Yap, Gratton and their colleagues return to the basics in a sense, looking into whether there is any link between the profiles of intestinal microbes and various clinical measures in autism disorder. The team used state-of-the-art DNA sequencing to analyze the presence, proportions and diversity of microbial species in stool samples from 247 children, 99 of them diagnosed with autism and 148 without a diagnosis of autism. They also have access to really very in-depth data that many other studies have not had access to, including clinical data, diet data, and genetic data. With this toolkit of methods, the team was able to gather very comprehensive information about these factors that can affect the microbiome. [ref. 3]

The next question the scientists ask themselves is: "for a specific characteristic to what extent is the microbiome generally associated with this characteristic?" It turns out that the overall profiles of the participants' microbiomes are strongly related to traits such as age, diet and stool consistency, Yap says, but the link to the diagnosis of autistic disorder itself is weak.

Looking specifically at the diversity of microbiomes, the team found a strong positive relationship with the diverse diet. Notabaly, this relationship existed regardless of ASD diagnosis, although children diagnosed with ASD were more likely to have a limited and poor diet than those without a diagnosis. The team also found that this diet appeared to be guided by certain ASD-related traits, including limited, repetitive behavior and sensory sensitivity.

This explanation seems plausible, according to Chloe Yap, "because if there are things you like to do over and over again, then maybe the same applies to food and you like to eat the same thing over and over again." Similarly, for sensory sensitivity, a child "may not like the sound of a certain food when chewing it, or the feeling of it in his mouth."